MY FEMINIST JOURNEY

After earning an MFA at the University of Colorado in 1969, I continued to paint on a regular basis. I wanted to be an artist but wasn’t sure what next steps to take. Fortunately, the feminist art movement guided me in the right direction. From 1974 thru 1979, I participated in three groups that raised my consciousness about being a woman artist and activist. They included Front Range Women in the Visual Arts in Boulder, Colorado and the Feminist Studio Workshop and The Dinner Party project in Los Angeles.

FRONT RANGE WOMEN IN THE VISUAL ARTS

In 1974, I was invited to join an organization called Front Range Women in the Visual Arts in Boulder, Colorado at a turning point when women artists around the country began to actively pursue a place among the mainstream art world.

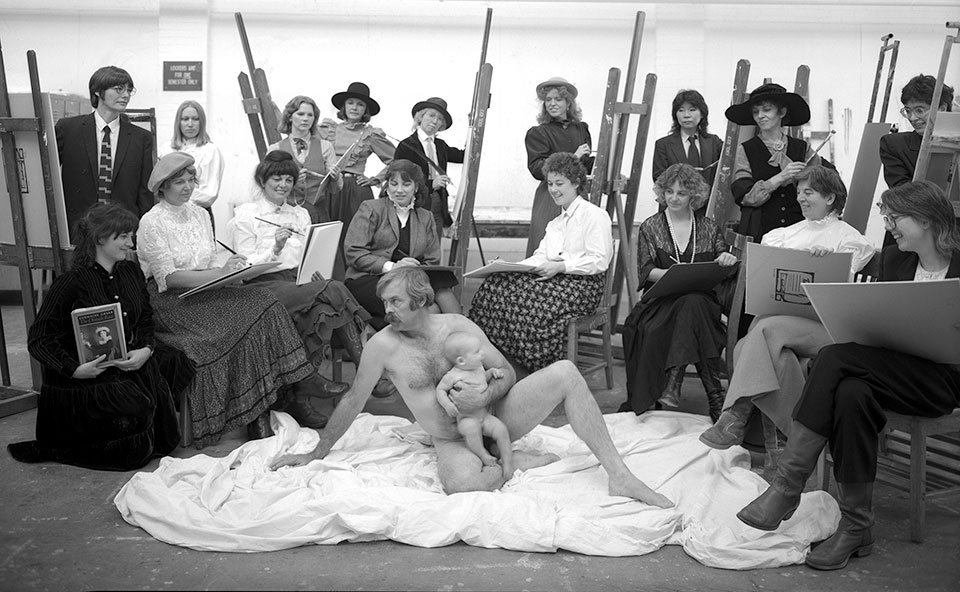

The focus of this organization was to lead the way to greater exposure for women artists, who had been historically overlooked by critics, galleries and museums. We gathered together to bring attention to our work through collective dialogue and support. This questioned the modernist doctrine celebrating the idea that art can only be divined and put forth through isolation. The photograph on the right shows how this group sometimes used humor to challenge female stereotypes.

THE WOMAN’S BUILDING

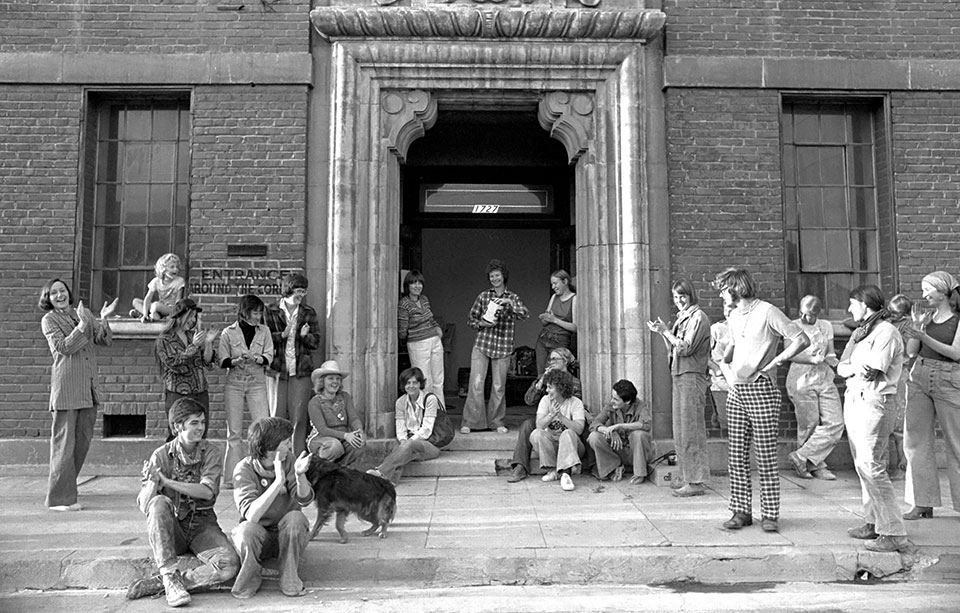

Group Photo of Feminist Studio Workshop students screaming with delight to be participating in a woman centered art education program. © Maria Karras, courtesy of Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2018.M.16)

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

The photograph on the left demonstrates the excitement and enthusiasm of the FSW students. I was elated to be immersed in an educational program that was woman centered in terms of both instructors and content. The curriculum focused on raising consciousness, creating dialogue and changing the culture.

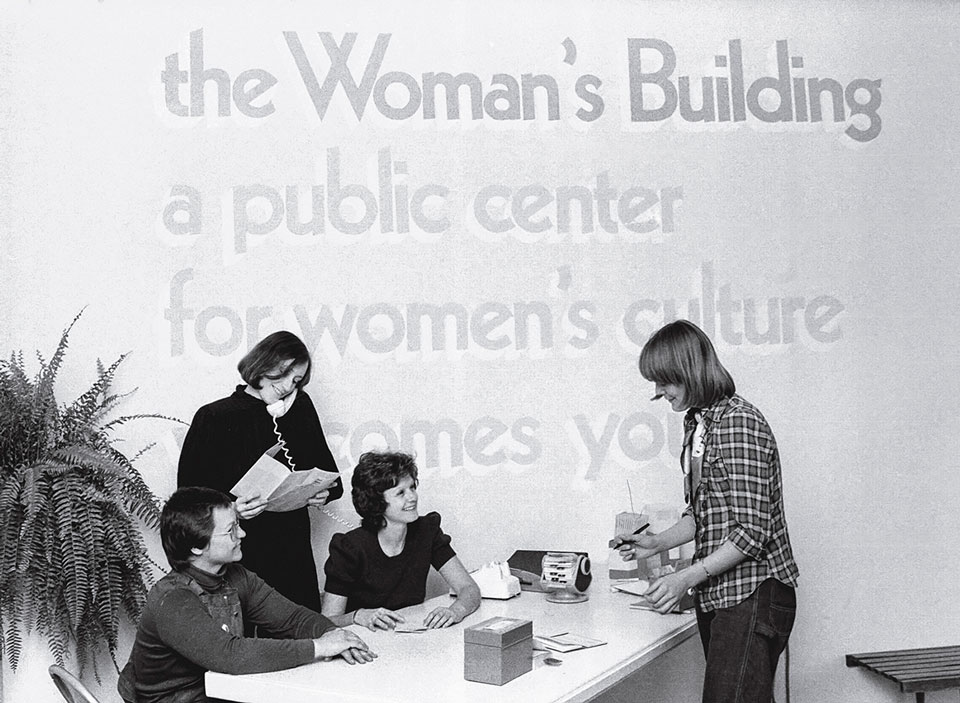

Sheila de Bretteville, Arlene Raven and Cheryl Swannack welcoming Cindy Marsh at the front reception area of the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles, CA in 1976. © Maria Karras, courtesy of Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2018.M.16)

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Women taking a well-deserved break during the renovation and hanging out at the entrance to the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles, CA in 1975. © Maria Karras, courtesy of Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2018.M.16)

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

THE DINNER PARTY, 1974-1979

Judy Chicago

I had been inspired by reading My Struggle As A Woman Artist by Judy Chicago when I was a member of Front Range Women in the Visual Arts. She was a woman who was finding her own way rather than trying to fit in with male artists. However, when I arrived at the Woman’s Building in 1975, she was not one of the instructors. I was disappointed but word was circulating that she was working on a project about women’s achievement in Western Civilization.

I didn’t meet Judy Chicago until the fall of 1975 when FSW art historian Ruth Iskin took a group of students to her studio in Santa Monica. Early work was already in progress on The Dinner Party project. Judy asked if any of us would like to volunteer to work with her so I signed up to help with the research.

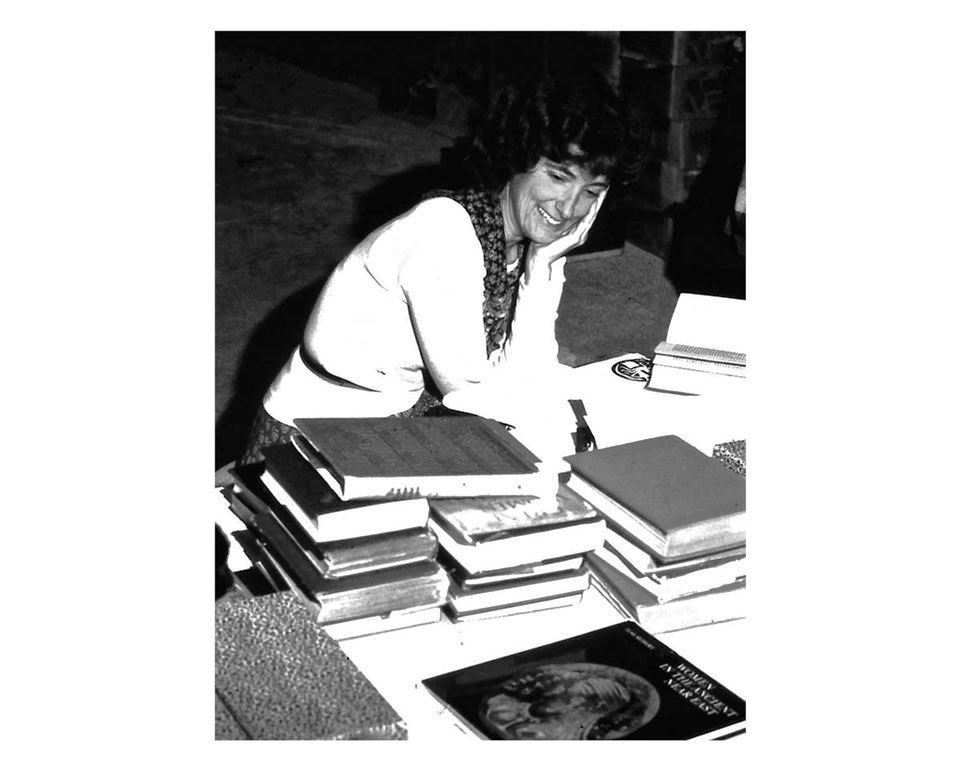

Judy Chicago signing a copy of her Kitty City book for Ann Isolde, photographer unknown.

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Most volunteers were drawn to the artistic work. However, I was there to obtain the education about the history of women that had been missing in my undergraduate and graduate work. I also realized that although there would be 39 china painted place settings on the table, the project would be far more meaningful if they were accompanied by another 999 names Judy wanted to emblazon in gold china paint on the Heritage Floor. This would be further proof of women’s contributions to history.

………………….

C L I C K I M A G E S T O E N L A R G E :

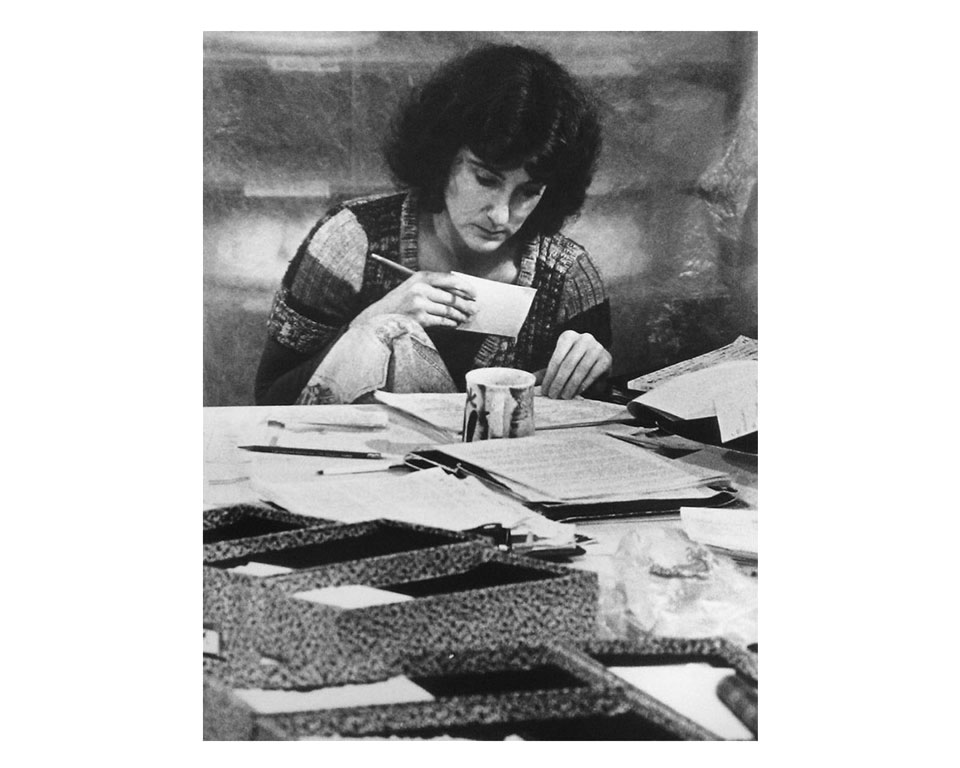

Ann Isolde in Judy Chicago’s studio with research books retrieved from the UCLA Library, 1975. Photographer unknown. Courtesy Through the Flower Archives.

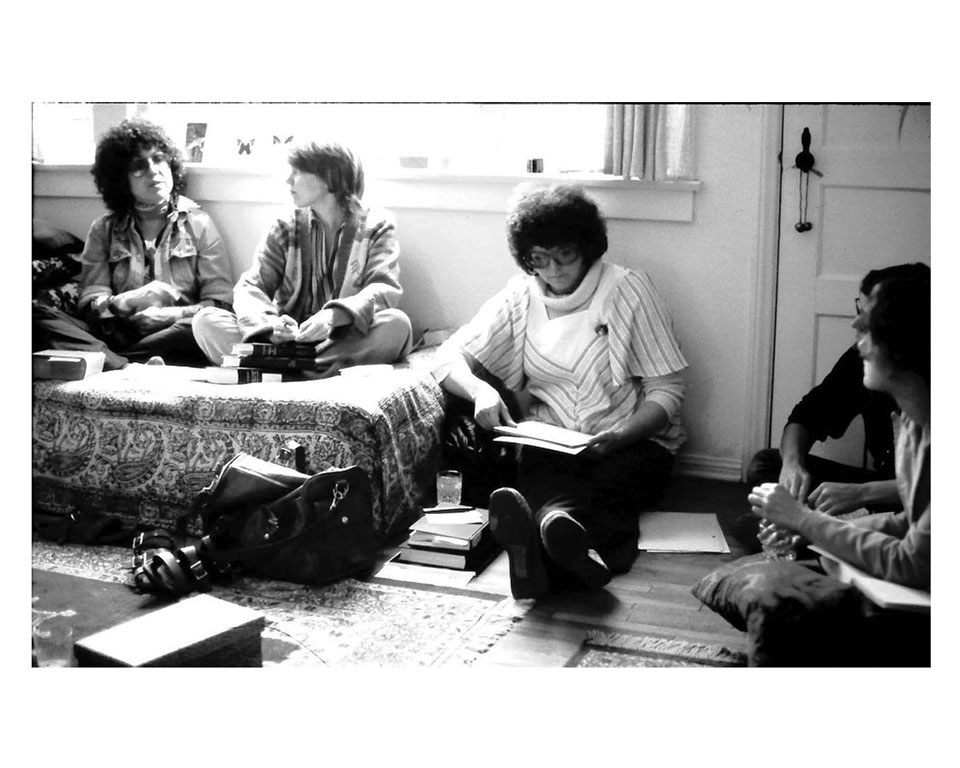

Judy Chicago advising research team members at Ann Isolde’s apartment, Santa Monica, CA, 1977. Photographer unknown. Courtesy Through the Flower Archives.

Ann Isolde in Judy Chicago’s studio researching women’s achievements in Western Civilization. Photographer unknown. Courtesy Through the Flower Archives.

Research Meeting in The Dinner Party studio, Santa Monica, CA, 1978. Courtesy of the Judy Chicago Visual Archive, Betty Boyd Dettre Library and Research Center, the National Museum of Women In the Arts.

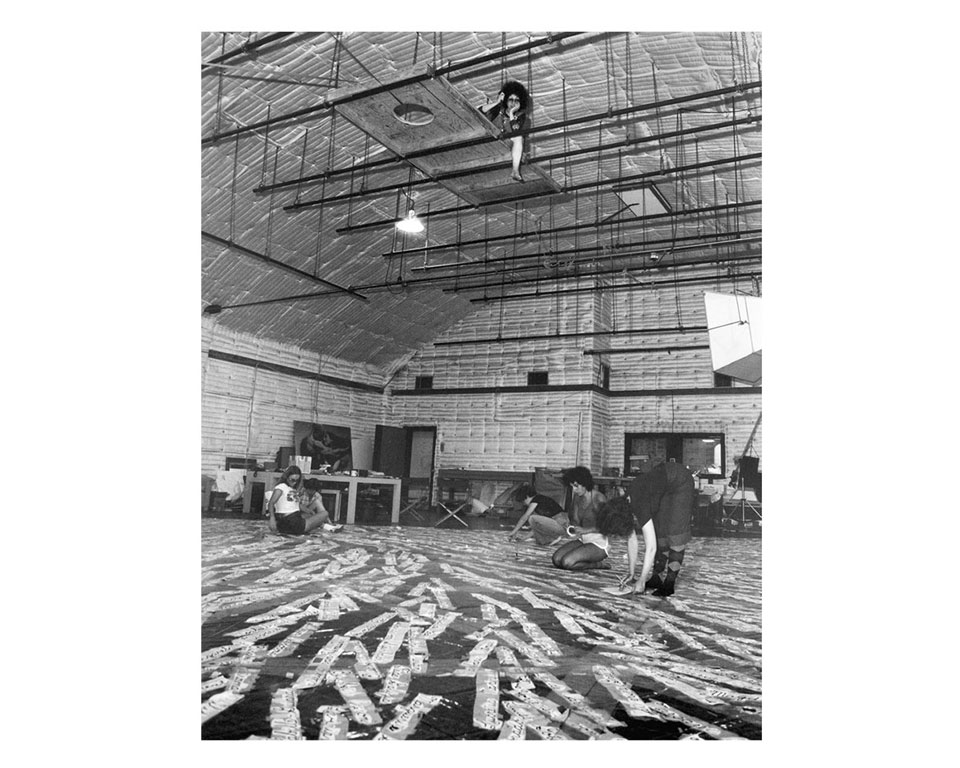

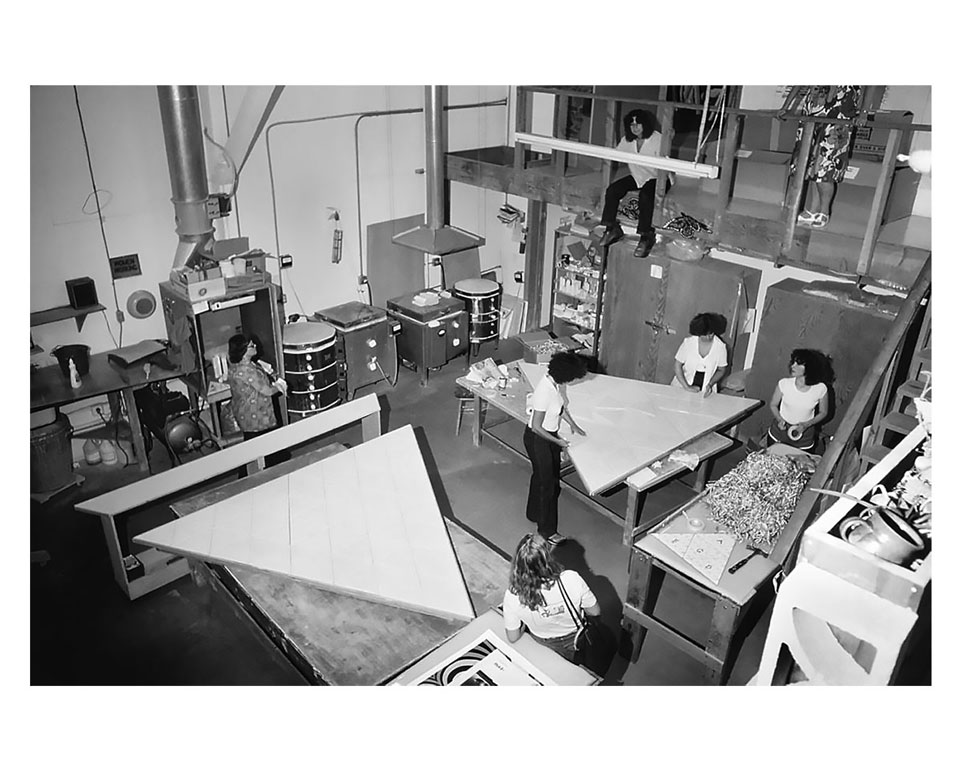

Participants organizing the Heritage Floor segments in The Dinner Party studio, Santa Monica, CA, 1978. Courtesy Through the Flower Archives.

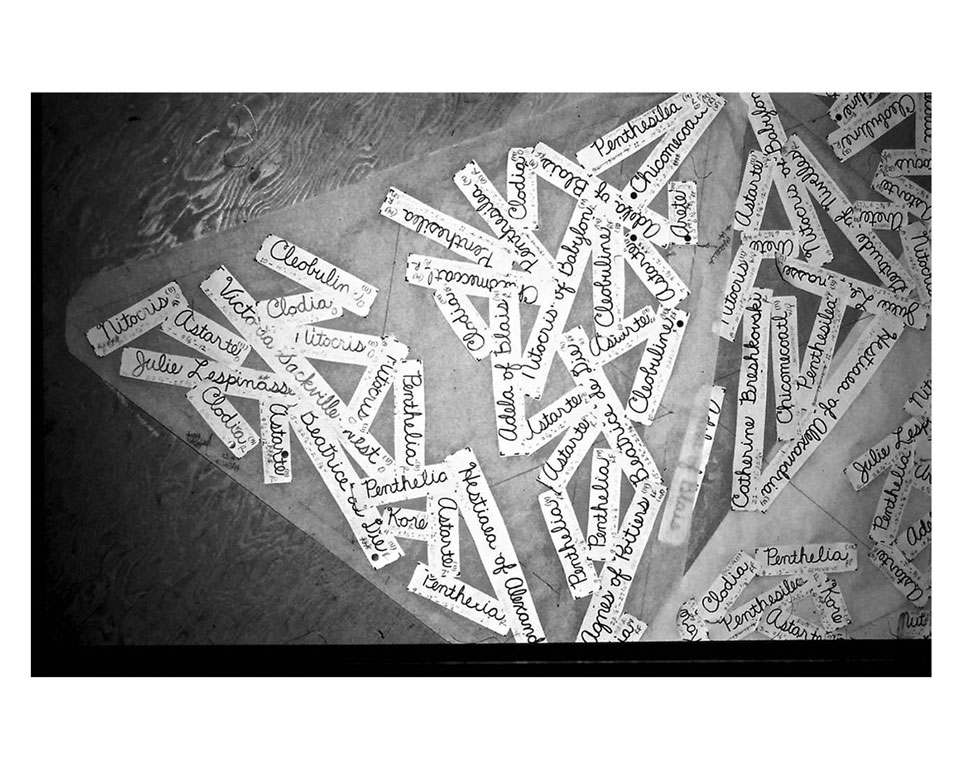

Participants sorting tiles and starting to paint names on the Heritage Floor in The Dinner Party Studio, Santa Monica, CA 1978. Courtesy Through the Flower Archives.

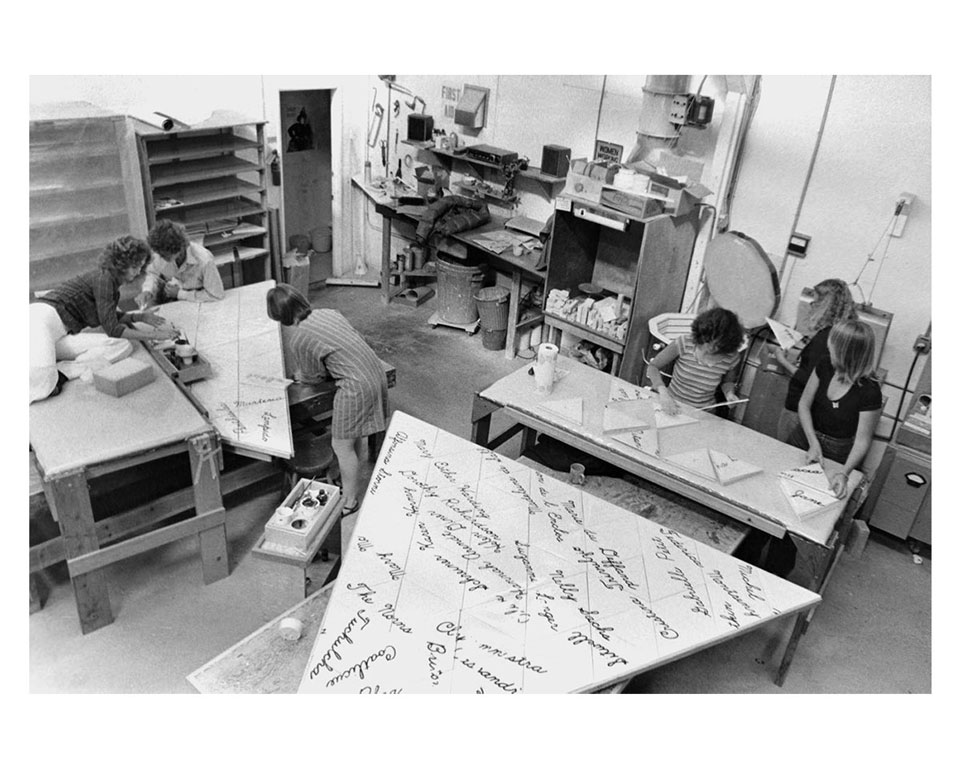

Participants continuing to paint names on the Heritage Floor in The Dinner Party Studio, Santa Monica, CA, 1978. Courtesy Through the Flower Archives.

Ann Isolde looking up while painting names on the Heritage Floor, 1978. Photographer unknown. Courtesy Through the Flower Archives.

………………….

Judy Chicago was aware that if you see yourself reflected in art and literature, this expands your vision of what you can be. So the primary goal of The Dinner Party was to create a revisionist version of women’s history. This was not an easy task and we would have been lost without a book titled Index to Women of the World from Ancient Times to Modern Times published by historian Norma Ireland in 1970. So we set out to research women in Western Civilization.

I eventually became the facilitator of the Heritage Floor research team. We collected information on over 3,000 women in Western Civilization and cross-referenced them on index cards by country, century and profession without computers. We debated the finalists who had to meet specific criteria to be included. After that task was completed, I finally put on my artist hat and was honored to be one of eight women who were selected to paint the names of the 999 women in gold china paint on the floor.